This is a feature-length piece, so you may wish to print off for the journey home or some such

Abraham Klein had his hands in his pockets. He was 36 years old and about to referee his first World Cup game. To one side stood Pele, Carlos Alberto, Rivelino and Jairzinho; to the other Bobby Moore, Bobby Charlton, Geoff Hurst and Gordon Banks. This was the grandest game, between the favourites Brazil and the holders England; the final before the final. The referee was an unknown Israeli. One report said that appointing him was “like sending a boy scout to Vietnam”.

Klein trusted his ability; so did Fifa. But anybody with an anima would have been nervous. He had refereed international games before. Only five of them, though, none anywhere near this stratosphere. This was a football opera, and his hands were trembling like a violin string. It gave a whole new meaning to the pre-match handshake. “I was very nervous,” he says. “My hands were shaking, so I put them in my pockets. I did not want the players to see how my hands were moving. Then I took them out and I decided to be strong in my body and in my hand.” He met both captains with an unyielding handshake, looked left and right and blew the whistle for the start of the match. His life had just taken an almighty fork in the road.

Cinderella as done by HBO

The past may be a foreign country, but that’s no excuse for xenophobia. The arrogance of modernity dictates that the best we have ever seen becomes the best that ever there was. How would we know?

It’s certainly true of referees. At the end of the 20th century, Pierluigi Collina was widely perceived to be the best referee in the history of football. Collina was a wonderful referee, surely the best of his generation; beyond that, we don’t really know. Suggestions that he was bald head and shoulders above all other referees is an insult to those who excelled before him – not least Abraham Klein, the marvellous Israeli referee who was generally accepted as the world’s best in the 1970s and early 1980s. In a piece in the Times during Italia 90, the veteran football writer David Miller said Klein was “probably the best referee for the past 20 years”. Alan Robinson, the overseas and services secretary of the English Referees’ Association from 1968 to 2004, described him as “the master of the whistle”. In the interests of balance, we must point out that not everybody concurred. Klein did not appear in Graham Poll’s list of the 50 greatest referees of all time, a list that includes – and you’ll like this – Graham Poll.

Klein’s is an astonishing story, pitched somewhere between feelgood fairytale and life-affirming quality drama; Cinderella as done by HBO. To say his is a life less ordinary doesn’t begin to do it justice. He survived prejudice, politics and even the Holocaust to reach the top of his trade. He made his World Cup debut in one of the tournament’s most famous matches - when, in referee years, he was barely out of short pants. He missed the 1974 World Cup because of the Munich massacre of his fellow Israelis two years earlier. He was scandalously deprived of the World Cup final of 1978, punished for his own scrupulous excellence. He ran the line in the 1982 World Cup while not knowing whether his son was alive or dead. He overcame all that to be regarded as peerless. No wonder he says determination is his strongest characteristic.

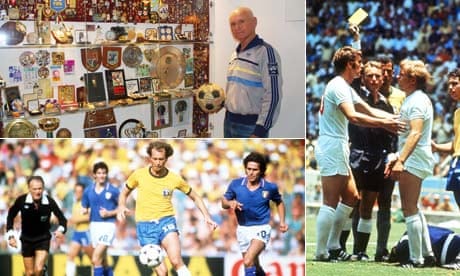

It would be enough to take decades off most men, yet Klein is a miracle of fitness and optimism. He turns 78 on 29 March, but his physical and mental sharpness defy his age. He is still the same weight as he was when he refereed Brazil and England in 1970. Look down at your stomach now and imagine that it will be the same in 42 years’ time. Exactly.

Klein is the type of person who sees the good in everything and everyone (except baseball, a rare hate). When we talk, back in January, he is full of the joys of Novak Djokovic versus Lleyton Hewitt in the Australian Open. “Wonderful tennis. What can I tell you?” Even on the phone from the other side of the world, he radiates an avuncular wisdom. He has a habit of saying, “I must tell you …”, and when he does you feel like you are settling down for an audience with Mr Miyagi. Klein is also unfailingly polite; when you say matter-of-factly that he was the world’s best referee, he says simply, “Thank you, thank you”.

If this paints a picture of Klein as a soft man, don’t believe it. He has an innate toughness that allowed him to control matches with natural authority in an age when hard man roamed the green with malevolent intent. That, and a level of preparation that would put most modern referees to shame, never mind those 30 years ago, were two of the keys to his success.

Klein has the lovely habit of talking in the present tense, with a voice that – although his generally excellent English is occasionally broken – you want to present verbatim. He regularly uses the phrase “I feel it”, testament to the sixth sense that served him so well on the field. Another of his favourite words is “unbelievable”. This is no Chris Kamara-like tic. Klein’s story is one you wouldn’t dream of scripting.

‘Don’t eat all the bread!’

Timisoara is often described as the most beautiful city in Romania. A piece in this paper spoke of its “bold, age-worn architecture”, “handsome, cracked grandeur” and “wealth of genuinely grand Habsburg buildings”. This gallery shows that your retinas could do a lot worse. Yet sometimes beauty is in the mind’s eye of the beholder. There is no beauty for Abraham Klein. Timisoara is where he was born and spent his first 13 years, six of them during the second world war. “My memories from that city are so bad that when I was in Romania as a Uefa observer two or three times they ask me if I want to go to Timosara to see my city,” he says. “I told them, ‘I don’t want to go’. What I remember, I don’t want to remember again.”

Klein eventually escaped Timisoara, one of 500 children who were put on a train to Holland. “My mother was still alive,” he says. “Many of my family were killed in Auschwitz, in the concentration camps. My father was lucky that he left Romania in 1937 before the war starts. When the war starts it was impossible to leave the country with my mother. For five years it was very difficult for us. My mother had six sisters; we lived with them and the parents in two rooms. The situation was not the best.” It’s so far beyond our comprehension that there’s no point even trying to empathise.

The train journey took three weeks, with very little food and no parents; those who were still alive had to stay in Romania. The children were taken to a school in Apeldoorn – “a very small place in Holland, a beautiful place” – where they would stay for a year. “I remember the first meal we had. It was lunchtime after three weeks on the train. When we arrived at the restaurant there was plenty of bread on the table. We run inside, all the children, we start eating the bread. Then they come to tell us, ‘Wait, wait, we have plenty of food – we have soup, milk, potatoes. Don’t eat all the bread!’”

The memories are some of the happiest of Klein’s life. “I must tell you that whenever I come back to Holland, I go to see Apeldoorn.” After a year, he went to a kibbutz in Israel, then back to live with his parents in Haifa. “I come to the conclusion that the life in a kibbutz is not for me.” The kindness that he found in Apeldoorn tattooed itself on his soul. “There are things in life that you cannot forget. When, after the second world war, a country like Holland gives you the feeling that you are at home; when they give you everything: food, education, sport, etcetera, etcetera … these are things that you cannot forget. It was something unbelievable.”

Preparing to succeed

Abraham Klein was not supposed to be a referee. He loved football and wanted to be a footballer. His father had played for MTK Budapest in Hungary; Klein was good, but not up to that standard. Serendipity did what needed to be done. In the mid-50s, on a break from army duty, his parents sent him to buy some trousers from a tailor called Jonas. Jonas was about to leave to referee an amateur game. He told Klein to come with him, and that he would make his trousers after the game.

Jonas turned an ankle during the match. He asked Klein to step in.

“I told him, ‘I don’t know the laws of the game’.

‘But you’ve played the game?’

I told him, ‘Yes I was a player, not the best but I know what is a foul.’

So he said, ‘The laws of the game are very simple, it’s not university. Somebody make a foul, you whistle.’

‘That’s all?’ That’s all the laws?’

‘That’s enough for this game.’

Klein showed such natural aptitude for refereeing, and such enjoyment of it, that he soon took the formal refereeing examinations. He would catch up with Jonas more than two decades later. Jonas later moved to New York, and found Klein among 60,000 people at a New York Cosmos game. “But,” said Klein in this interview, “he didn’t have my trousers …”

By then, Klein was wearing the trousers on the field of play. He rose through the ranks, refereeing army games, youth games, Israeli league games – and even the first meeting between teams from West Germany and Israel. In 1969, Hapoel Nahariya played against an amateur German team named Bayern Hof. Klein had no idea of its significance until he was interviewed by a German TV company 40 years later for a documentary.

He had refereed his first Israeli league game in 1958, at the age of 24; six years later he graduated to international football, when Israel played a friendly against the Netherlands. In 1965, at the age of 31, he was given his first major game: Italy v Poland in Rome. It was on a scale previously unimaginable. The biggest grounds in Israel held 20,000; now he would be officiating a World Cup qualifier in front of 80,000. Klein decided to take matters into his own hands – a week before the match, on his own initiative and out of his own pocket, he went to watch Roma play Napoli at the Stadio Olimpico.

“I decided, alone, to take a plane in the morning,” he says. “I come back late with Alitalia, 10 o’clock at night I remember. I went to the game, I bought a ticket; nobody knew that I was there. I was in the stadium with the people, in the crowd, and I feel the weather, you know; I feel how they behave. I was shocked, because 80,000 people were shouting and crying.”

He was not shocked a week later when he returned for the Poland game. Klein’s preparation could not have been more thorough. He learned as much as possible about the players – this in an age before computers, never mind the internet, and when phone calls overseas were extremely expensive. Klein wrote to a friend in Poland, asking for information on their team, and persuaded Gazzetta dello Sport to send him a series of cuttings. “They wrote everything every day about everybody,” he says. “They know more than the family about the player.” He learned that Gigi Rivera was a star player “and that the defenders try all the time to kick him”. Klein, always a keen exponent of the advantage rule - “one of the most beautiful things in the game” - vowed to play it wherever possible. Three of Italy’s goals in a 6-1 win came from advantages. The Fifa observers at the ground took notice.

Throughout his career, Klein was not prepared to fail. The level of his preparation, both physical and mental, was extraordinary. He was not years ahead of his time; he was a generation ahead. “It’s a good advantage – not just in refereeing but in everything in life – if you know the person who is standing before you,” he says. He would study hours of videos to see what tactics the teams used, which players dived, which tried to bully opponents or referees. In 1970 he arrived early and spent a fortnight in the Camino Royale in Guadalajara, acclimatising and studying teams.

“I know the tactics of the Brazilian players,” he says. “I saw that inside the area – or just outside, because of Rivelino’s free kicks – that if it was shoulder to shoulder they would be very close to the grass. If you remember the [England] game, [Alan] Mullery with Pele inside the area, shoulder to shoulder and Pele was down. So I tried to learn everything, and also the behaviour when you make your decisions.

“Before every tournament I try to learn the language. Of course I know Hungarian, my mother language (Timisoara was originally part of Hungary), and Romanian. I speak some German, not the best. I learn Spanish, French, Italian because at school I learn Latin so it’s very simple. I understand not 100%, but if I understand more than 50% when I read sport magazines, that is enough.”

He understood 100% about diet and exercise. In his 1995 guidebook for officials, The Referee’s Referee, Klein goes into rare detail about his preparation. Everything is explained down to the last carbohydrate portion, the last check of your pulse rate, the last 2,000-metre jog and the last 50-metre sprint (backwards, this time, to simulate match conditions). In the mid-1970s, when Prozone was but a glint in Sam Allardyce’s eye, Klein measured that he ran seven and a half miles in a match.

Before that Mexico World Cup he climbed mountains in Israel to help cope with the altitude; before the Argentina World Cup eight years he trained in a similar climate in Cape Town. In 1982, concerned that, at the age of 48, his fitness was not what it should be - “the passing of time started to put marks on my body” - he commissioned a physical trainer called Jacob Almor, who prepared a bespoke program.

“It was based on gradually increasing my stamina and my physical conditioning,” wrote Klein in his 2010 autobiography, The Master of the Whistle. “It included long-distance running on sandy beaches and on hard surface streets of my town, Haifa. Long-distance endurance cycling and short speed sprints on an athletic field as well as utilising a gym, where weight lifting and rubber-bands equipment helped my load endurance and flexibility. We started slowly but then picked up the tempo. The training was intense twice each day, mornings and evenings. It was murder; very hard; plenty of suffering for a 48-year-old chap. I shed nine pounds in four weeks and prepared my body for 120 minutes of a physical stress load so as to allow me proper refereeing stamina for extra time, just in case.”

Almor wanted no money, and said it would be an honour to help Klein. But always the preparation was done off Klein’s own bat and, when necessary, out of his own pocket. In his day referees had to pass the Cooper Test – running 2,600m in 12 minutes – as part of their preparation. When he later became chairman of the referees’ committee he immediately upped it to 3,000 metres. “I told the referees: you must be fitter than the players, because there are 11 players on the field. You have to be in the right position. A striker can miss a goal, but if a referee misses an incident it can be catastrophic. Some very, very famous referees – I don’t want to tell you their names – made some bad decisions in World Cup games. It was their last World Cup. I made mistakes in my country in some games, I know, but I couldn’t afford for 1970 to be my last World Cup.”

Learning from those mistakes was a key part of his development. “The first analysis is the most important thing after the game – to learn, and not to think you are the best in the world. When I met my wife she told me: every time you can do better. And she is right. You can do better in everything. When I made a mistake, then I try to avoid these mistakes again. I had a semi-final in Tel Aviv when the ball was not over the line but I was in a poor position and awarded a goal. Everybody wanted to kill me.

“In Italy v Brazil in 1982 – the last moment of the game - you can see Dino Zoff on the line with the ball [after saving Oscar’s header]. I had an excellent view. You can see the Brazilian players wave their hands that the ball is in, but you can see me wave that the ball is on the line.”

In the last minute of his last World Cup game as referee, Klein’s immaculate preparation had paid off one last time.

Emotional intelligence

Abraham Klein arrived in Guadalajara in late May 1970. For the next two weeks, he ignored the not inconsiderable temptations of a fascinating city, and concentrated on his usual preparation. “I didn’t leave my hotel for two weeks, even for one day, to see the city,” he says. “I didn’t see the city at all, only the hotel and the stadium. I want to concentrate only on the game. I know that I cannot have a bad game. It was very important for me because I know that, coming from a small country, I have a big responsibility to the Fifa members who appointed me to the game. Later I ask Sir Stanley Rous or Ken Aston (the Fifa president and chairman of the referees’ committee, respectively) why they chose me. I was a very young referee with no experience, only five international games. Aston always told me: we trust you, you are honest, you make good impression and you are in good physical condition.”

Klein wasn’t plucked out of thin air; he was picked because he could cope with thin air. He had shown that during the Mexico Olympics in 1968, and Fifa knew he was fit enough to cope with Mexico’s oppressive heat. England’s Terry Cooper would lose 12 pounds in the match. For Klein it was squeaky-bum time in more ways than one. He still had the problem of being perceived as the boy scout in ‘Nam. The players of Brazil and England did not know who he was. “In the first moment, they look me: ‘Who is standing here in the middle of the field?’ They knew nothing about me. I try from the first moment to respect the players; I look their eyes. A little later during the game they understood that they must also respect my refereeing.”

He controlled the game calmly from the first whistle. It flowed gracefully from end to end, a festival of goodwill and mutual respect, and is still one of the World Cup’s iconic contests. “A referee is feeling during the game and after the game, how is he refereeing, how is his performance. If you make a mistake, you alone know immediately. You feel it: you feel it because of the behaviour of the player, you feel it when you watch the coach. I’m not talking about [José] Mourinho; he always protests against the referees. You have some coaches who you respect. If they wave their hands once every 10 years you think about it. But I feel very good in that Brazil/England game.”

There were a couple of major incidents. Francis Lee was booked for a late challenge on the goalkeeper Felix; then, just before half-time, Pele fell in the area after a challenge from Alan Mullery. It would have been so easy, too easy, for a young referee to be seduced by the greatest player in the world. Klein simply waved play on. He later called it “the best decision of my life”.

His performance received universal and divine haskamah. “It was a tough game,” said Pele, “but he always had total control of the action.” In his Story of the World Cup, Brian Glanville said the game was “admirably refereed by the obscure Israeli referee Abraham Klein, an inspired appointment”.

What was most striking was his apparently effortless authority. Unlike some of the other great referees, Collina and Jack Taylor in particular, Klein did not have physical authority. He was 5ft 5in, a fraction over 10st. But he could impose himself in other ways. He was a big believer in body language; a firm handshake, a perfectly upright stance, a decisive signal or whistle; and eye contact, always eye contact. It soon became apparent he did not suffer insolence or indiscipline. He was the teacher you knew not to take liberties with. In a sense, his control was supernatural. After that Brazil game, the Fort Scot Tribute said he “showed he had the mysterious and decisive power to move into an explosive situation and calm then down by the simple exertion of cool authority”.

He could impose himself physically, in his own little way. Before one game, Klein was inspecting the footwear of a notorious troublemaker and decided to squeeze the player’s wrist. “I merely applied a little bit of pressure, ever so slight, so he knew I was making a point: we’ll have no problems today, will we?” During an NASL game, when Johan Cruyff was faffing, refusing to retreat 10 yards at a free-kick, Klein jolted him into compliance with a zesty blow of the whistle only a couple of yards from Cruyff’s earlobe.

“You either have authority or not,” says Klein. “I didn’t need to give red cards. I feel that I was able to control the game and the players respect my decisions. I was very happy [that I did not have to give too many red cards]. I felt that the most important thing in the game is that the players respect me; if you gain their respect you can do what you want in the game.”

His control of games came in no small part from his amateur psychology. Later, after reading the work of Daniel Goleman, he could give it his own name: emotional intelligence. “Goleman wrote in his book one thing which I think is very important: that to be successful in your life you need to have emotional intelligence. You have it or not; you cannot learn this; you cannot go to university for this. I know many people, many famous referees – I do not want to give you names as it is not very nice – who did not finish high school, yet they were excellent referees. They have emotional intelligence, because they feel what other people think, and can imagine what the other person is going to do. You have many politicians and businessmen: they are not intelligent, but they are very successful in what they do in their life.

“I think you can learn how to prove your authority, but you must have your authority in the first place. You can see it with Jack Taylor. I can’t remember a player that has come close to him. He’s a tall man, like a rock, and when he looks at players – they run away! He has it, you know. I don’t know what he is doing today. Give my best regards to him, I love the gentleman.

“Jack Taylor was the best referee I ever saw in my life. I learned a lot from him. I remember when he refereed the World Cup final in 1974 and awarded the penalty kick against West Germany, and Franz Beckenbauer just start to come close to him. I saw him stood like a rock with his hands waving, and Beckenbauer - one of the biggest players in the world – left immediately, he ran away from there.

“This is the referee for me. Even if he makes a mistake, the players respect him, everybody respects him. This was [Pierluigi] Collina, this was Jack Taylor, this was [Karoly] Palotai, this was Leo Horn. These four referees in my opinion were the greatest referees.”

The authority of Klein’s performance in the England/Brazil game impressed everybody. “Whenever people introduce me, even now, they say, ‘Abraham Klein who refereed England v Brazil’, not Brazil v Italy or Italy v Argentina.” The pride Klein takes in his career is evident throughout – not just on a personal level, but because of what he achieved on behalf of a small football country. After the game he paid a local photographer $100 - “at the time it was big money for me” - for a negative of him tossing the coin with Carlos Alberto and Bobby Moore. It is one of hundreds of items of memorabilia on display in a little museum at his home. It includes the match balls from England v Brazil in 1970 and Italy v Brazil in 1982; a series of cards on which he is photographed with the likes of Alberto, Moore, Dino Zoff and Karl-Heinz Rummenigge; rosettes; a silver plate signed by the Italy squad of 1982; a watch with a dedication from Ken Aston (“you never let me down, not as a referee and not as a friend”; and even a toiletry bag from the Scottish FA. Every memento tells a story.

He has a less welcome memory of the 1970 World Cup: Montezuma’s revenge, which meant he had to pull out after originally being awarded the quarter-final between Italy and Mexico. “I was very, very, very upset because I feel good after the Brazil game.” His mood was improved when Sir Stanley Rous told him: “It’s not your last World Cup.”

Klein was paid £10 for refereeing the game. In the future he was lucky to get that; at the 1982 World Cup the referees were paid only expenses. Back then – and this will be hard for younger readers to understand – people really did do it for the love of the game. He never gave up his day job as a PE teacher. “Money for me was not important. To have a game like England-Brazil or Italy-Brazil is much more than a million dollars. Believe me, if I had a million dollars at that time and they asked me if I want pay a million dollars to referee Brazil v England, I would write a cheque. It changed my life.”

It not only changed his life; it came to define it. “I feel very good with this, believe me. I live this game all my life, more than any other game.”

A great and serious mistake

The letter cut straight to the point. It was written in 1995 by Ken Aston, the former chairman of the Fifa Referees’ Committee, and addressed to Klein.

“Thanks you for your book … It is a great shame that you made a great mistake in your refereeing career. A very serious mistake which you could never recover, and one which everyone connected with the appointment of referees at international level remembered. And what you ask was this great and serious mistake? Simply that you were an Israeli. I must tell you that had I still been chairman of the Fifa Referees’ Committee in 1982, you would without any doubt have been carrying the whistle and not the flag. I was happy to have been able to support you throughout your career simply because you deserve such support.”

Politics cost Klein the World Cup final in 1978 (and perhaps 1982), a place in the 1974 tournament, and permeated his career. There was, at first, a mistrust of a referee from a small league, although that kind of prejudice was the least of Klein’s worries. In 1981, when he went to French Guiana as part of the Fifa Coca-Cola Project, he was originally refused admission because Israelis were not allowed. When the rest of the Fifa party said they would get on the first return flight unless Klein was allowed in, the authorities relented. Far more damagingly, the Munich massacre of 1972, in which members of the Israeli Olympic team were taken hostage and killed, meant it was not safe for Klein to go to West Germany for the World Cup two years later.

Israel did not become a member of Uefa until 1990, so there was no chance for Klein to officiate major European league games. He does not have any grievance and says that Fifa “were 100% correct with me”. If he couldn’t quite access all areas, he at least got to go backstage. “No Israeli was allowed to officiate in the east countries in Europe, but I refereed USSR twice. I also refereed Cuba v Poland in the opening game in the Montreal Olympics, all the communist countries I was not allowed to enter. Fifa let me referee these nations when they play abroad.” He also refereed the Intercontinental Cup match between Nottingham Forest and Nacional in 1980.

Klein became a whistle for hire (although ‘hired’ is a generous term given the amount he was usually paid). He refereed around 100 NASL games in four seasons, and covered nine games at the Mini World Cup in 1972, six as referee - including a quarter-final, semi-final and the final – and three as linesman. This was a particularly impressive achievement; shortly before the tournament Klein lacerated a muscle, had to put his leg in a cast and was told to forget about participating.

There was also a seriously awkward World Cup qualifier between Italy and England in 1976). There had been a climate of mutual mistrust for years, which exploded in a nasty match at the US Bicentennial Tournament six months earlier. With the stakes so much higher in Rome, Fifa called for its top man. The Sunday Mirror described Klein as “the man with the most unenviable job in football”. He dismissed as “nonsense” reports that he had been visited at his home by Italians, and said simply: “The game doesn’t worry me.” It worried almost everyone else. A bit of the old ultraviolence seemed inevitable. “If all that Abraham Klein has to watch this afternoon is tongues,” wrote David Lacey on the day of the match in the Guardian, “he will be fortunate.”

Klein, on advice from Aston, used the advantage sparingly. It meant more fouls than usual – 48- but a game that never got out of hand. “The game, while hard, was refereed firmly and sensibly by the Israeli Abraham Klein … who was quick to clamp down on anything that might provoke retaliation,” said Lacey in this paper. The Mirror said he ruled “with an iron hand”. Klein’s excellence gave a lie to the old adage to the referee should be invisible. You couldn’t fail to notice that you hadn’t noticed him.

Instead of becoming notorious, the match is now remembered for a classic goal from Roberto Bettega in Italy’s 2-0 win. After the game, he received another letter from Ken Aston:

19 November 1976

My dear Abraham,

Bravo, well done. Mrs Aston said to me, ‘Abraham didn’t let you down’, and she knows how important it is to me. The fact that England lost does not perturb me in the least; it might be said that Italy were the better team, and certainly they were, but the best team was the third team of match officials. Please pass on to your two colleagues my congratulation …

Klein covered so many great games around the world. But he never refereed a World Cup final.

A real hero

The English tabloids have not always been known for their support of foreign referees. The hounding of Urs Meier after Euro 2004 was a disgrace, while Tom Henning Øvrebø was openly ridiculed when he made a mess of the 2009 Champions League semi-final between Barcelona and Chelsea. Thirty-one years earlier, the tabloids had only kind words for Klein. Particularly the Daily Mirror. “The first authentic hero of the 1978 World Cup has emerged at last – and it is not a pampered, overpaid professional footballer,” wrote Frank McGhee under the headline ‘Abraham restores our faith’. “He is Abraham Klein of Israel.”

Klein was praised worldwide for his immaculate performance in the group game between Italy and the hosts Argentina. With both teams having qualified for the second phase, it might have seemed like a nice easy dead rubber. It didn’t quite pan out that way. Klein says it was the most difficult game of his career.

At the time Argentina was run by a military junta, and the sense persisted that anybody else winning the World Cup was simply not an option. After they beat Holland in the final, one of the Dutch players said that his side would not have got out of the stadium alive had they won. He was only half joking. You can’t overestimate how intimidating it was. In Argentina’s first two games, 2-1 victories over Hungary and France, the referees had caved in to the relentless pressure of 77,000 shrieking fans.

Hungary had two players sent off; France conceded a dodgy penalty and didn’t get a much clearer penalty of their own. “You can ask Platini what he thinks about that game,” says Klein. “You can ask Hungary for their opinion about that game.”

Argentina needed to beat Italy to stay in Buenos Aires for the second group stage. In his History of the World Cup, Cris Freddi said that Argentina’s “excesses were kept in check by the best referee in the world”. Italy won 1-0. “The crowd were very upset. I had no problem with the players; they respect me. The crowd, you know, they pay and when they pay they can tell you whatever they think about you and your mother.”

Klein turned down a couple of penalty appeals just before the break, which led to vicious abuse either side of half-time. This time his hands were not in his pockets. He strode off the pitch knowing he had made the right decisions, a proud monument of conviction and moral courage. “When I’m on the pitch, only two things are important to me: being fair to both teams and making my decisions bravely,” he told Simon Kuper in Ajax, The Dutch, The War. “I think all referees are fair, but not all of them are brave, probably.”

He looked the beast in the eye and did not blink. “There was nothing more impressive in this World Cup,” wrote Brian Glanville, “than the way he stood between his linesmen at half-time in the Argentina-Italy game, scorning the banshee whistling of the incensed crowd.”

This is not to say Klein was entirely unaffected by the abuse. He is human and he needs not to be hated. “The feeling is very bad,” he says of his reaction at half-time. To avert a similar reception, he decided to delay his return on to the field. Instead of leading the players out, he let the Argentina players go first; his return was lost in the hero worship. It was an ingenious and highly successful manoeuvre.

“I felt stronger in the second half because I know all my decisions were correct. I feel very good with this. Even after the game, they told me, ‘don’t go out, the crowd is waiting for you’. I told them, ‘I’m not afraid’. I was never afraid in my career. I know that the crowd will do nothing after the game. I was not afraid to do what a referee must do in the game. There was no problem.”

He keeps a scrapbook full of praise for his performance:

‘Diesmal kein Heimschiedsrichter’ (“No home-favouring ref this time”).

“Abraham Klein from Israel, who was unwaveringly insistent on applying the laws as they were written - with the resultant hail of abuse from the home country, when they lost, and widespread acclaim in Europe. Ironically, his brave, conspicuous performance robbed Klein of his rightful claim to the final.” (From The Argentina Story by David Miller)

‘Il miglior fischietto è Klein’ (“The best referee is Klein”)

“I hope the brave, little Israeli ref, Abraham Klein, gets the final.” (Brian Glanville in the Sunday Times)

‘Ganz gross, Herr Klein!’ (“Fabulous, Mr Klein!”)

The comments were echoed in the Guardian. “Italy produced a marvellously balanced and co-ordinated performance to beat Argentina,” wrote David Lacey, “and much of the credit for creating the circumstances in which they were allowed to do so must go to Abraham Klein, of Israel, whose firm, fair refereeing was precisely what the situation demanded.”

In the Mirror, Frank McGhee said “he didn’t make a single wrong decision in the whole 90 minutes of a marvellous match … My most abiding memory of the match is the way both teams queued up at the end to shake hands with Klein. They knew, we knew, he had done most to make it a match to remember.”

After another excellent performance in the second group stage match between – of all teams - Austria and West Germany, he seemed a certainty for the final. Pele thought it; Jack Taylor thought it; even educated fleas thought it. But it went to the Italian Sergio Gonella – reportedly on the casting vote of another Italian, Dr Artemio Franchi, the chairman of the referees’ committee. Klein’s consolation prize was the third-place play-off between Brazil and Italy. Clive Thomas, the Welshman who also referred at the tournament, called the decision an “utter disgrace”. Cris Freddi also described it as “disgraceful” in his World Cup history.

“To tell you the truth I was very disappointed,” Klein says. “I think at that time I was fit to referee the final. But only one man can referee the final, and if I look back I am still happy with what I had in my life, in my refereeing life.” Klein is certain he would have had no problem being impartial, despite his affection for Apeldoorn.

Gonella lost control of the match even before it started, with the kick-off delayed by over 10 minutes by Argentinian gamesmanship. First they came on to the field late; then they complained about the bandage on Rene van de Kerkhof’s arm, even though he had been wearing it all tournament. The match was a nasty affair. Argentina did what they had been doing most of the tournament; Holland showed us why Netherlands is all but an anagram of neanderthals.

There are a couple of theories for Klein’s rejection. One is that Argentina protested about his links with Holland. It sounds good, but at that stage nobody knew of his year in Apeldoorn. “Nobody knew because nobody asked me,” he says. “Nobody at the Argentinian government or Fifa knows about it, so this cannot be true.”

More likely is that he was punished for his performance in the Italy game; that Argentina bullied Fifa into picking another referee. “Maybe this was the reason,” he says. Either way, there is a startling lack of bitterness. “Some of the journalists told that some of the members of the referees’ committee wanted me, but I cannot tell you one wrong about the referees’ committee or the Fifa president. They support me throughout my career. You cannot find many referees from small countries who had the games that I had. I refereed Brazil seven times, Italy seven times. They gave me the best games in the world. Maybe Gonella was better than me.”

The bell rings

Klein knew about control. For over a decade, he had controlled the best players in the world. He thought he knew about control. He was wrong.

“It is the one time I lost control,” he said. He was sat in a hotel in Spain, preparing for the World Cup. He had no idea where his son was, or whether he was alive.

After 1978, Klein was due a quiet, trouble-free World Cup. Some chance. First came yet more politics. With Kuwait and Algeria having qualified, Arab TV stations threatened to boycott the World Cup if an Israeli was allowed to referee. On 15 March, when the referees list was to be announced, Klein paced around the room like a teenager waiting for a call from the one they mistakenly thought was The One.

“I kept fiddling and checking my phone,” he recalled in Master of the Whistle. “Is my line connected? Do I have a dial tone? As time passed by I have gotten more nervous, more morose. I was in agony and felt I was going crazy.” A few hours later came relief: Klein’s candidacy had been unanimously approved by Fifa’s referees committee, who had reached a compromise: his name would be erased from the screen during broadcasts to Arab countries.

After more bureaucracy – the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports originally rejected his application for leave – Klein prepared to depart for Spain. Then things took a darker twist. Palestinian terrorists shot Shlomo Argov, the Israeli ambassador for England, in the head. He was in a coma for three months. Retaliation was inevitable. Klein’s first born, Amit, was on active duty, but he reasoned with himself that a new recruit would not be in the firing line.

He landed in Spain and settled in for a few days. Then the phone rang on 6 June; his wife told him that the war was on in Lebanon, and that Amit was on standby. “Suddenly I went through a range of emotions that I never felt before; a worry mixed with fear,” he wrote in Master of the Whistle. “My body got numb and a cold sweat started to cover me head to toe. All I could do was to sit on my bed, feel sorry for Amit and for myself. And then uncontrollable tears started to come down my cheeks. For the first time in my life I was not in control; I lost it and it was a feeling I could not bear.”

The next day Klein found out that his son was in combat in the hot spot of Damour. He requested a meeting with Dr Franchi, the chairman of the referees’ committee, and told he was in no fit state to referee a game. “’Are you sure about this?’, he asked. ‘Yes I am 100% sure. My son is in combat in Lebanon. My family has not heard from him. We have sign, no word, whether he is alive. I am extremely worried about him and his whereabouts and therefore I do not feel like I am in the proper state of mind to referee a World Cup game.’”

Klein spent the first round as either linesman or fourth official. For nearly two weeks he had no word of his son. On 18 June he ran the line in Italy v Peru. “I did my job while my mind was floating. I felt like I was enclosed in some space bubble. Mostly my thoughts were with Amit.” That evening he returned to his hotel to find a letter waiting for him at reception.

Shalom dear dad,

Today is Friday and as you know it happens to be my birthday. I am celebrating it here in far away Lebanon. Everybody got recruited and called in. The Core of Engineers has been operating on the Litani for three weeks. Sadly a lot of guys that I knew got either killed or seriously wounded and my heart is broken. I am already waiting impatiently to see a World Cup game refereed by you (I wish to see you referee many games as well as the final). Here, everybody is collecting newspaper clips about the games and passes them on to me. Much success! We are all crossing our fingers for your success.

Love, Amit.”.

“I could not stop my tears,” said Klein. “It is difficult to explain to someone the emotions that father goes through when reading a letter from his son in combat. What a difference a sign of life in the form of a small letter can make on a parent.” Later he heard his son’s voice for the first time since arriving in Spain. “When the phone rang in my hotel room and I heard Amit’s voice on the other side I thought I was hallucinating: how the heck he has managed to reach me on the phone in the middle of a war to communicate with me? It was one of the most exciting phone conversations that I had ever had in my life. He was not on the front combat lines as I had assumed but his unit had done a considerable mileage on foot in search of the hidden enemy.”

His son implored Klein to return to refereeing. Amit Klein would go on to become an international referee himself, and today he is a Uefa observer. His old man wasn’t quite finished yet. He had been assigned to Brazil v Italy in the second stage. The magnificent Brazilians needed a draw to reach the semi-finals; an unconvincing Italy needed to win. Klein was peculiarly unexcited. He thought Brazil would win easily. He told his two linesman that “it will be a game that nobody will remember in a few months”.

“How wrong was I?” he reflects. He never refereed a World Cup final, but perhaps the greatest game in World Cup history is a decent alternative. When Paolo Rossi scored his second goal to put Italy 2-1 up after 25 minutes, Klein says “the bell rang” in his head. “I realised that I was part of history in the making.”

The heat and end-to-end nature of the game would have been too much for most 48-year-olds, but Klein’s fitness served him well. With the score 1-1, Brazil appealed for a penalty when Claudio Gentile pulled Zico’s shirt so hard that he almost ripped it off. The linesman had flagged a second earlier for offside, however. “If the linesman’s flag would not have been raised to indicate an offside call I would have whistled without a hesitation for a penalty and given Gentile a second yellow card. However, Zico had a hard time accepting my decision. He was furious with me and continued to show me again and again the great tear in his shirt. ‘So go change your shirt’ I told him in return.”

Italy went on to win an epic match 3-2, despite a furious late assault from Brazil that included Zoff’s save on the line from Oscar. “It was an invasion, like in Normandy, with all the players,” he remembers. Again he seemed a likely candidate for the final, but Fifa went for Arnaldo Coelho. “The obvious choice was Abraham Klein,” said Brian Glanville in his Story of the World Cup. “But the Referees’ Committee, pleased with itself and as incompetent as ever, compromised pathetically by assigning Klein to … the replay.” Klein was appointed linesman for the first final.

“In 82, the best referee of the tournament was Coelho, and I was very happy that I was on the line,” he says. “I was the first man to congratulate him and I told him I was very happy I was with him.” Had there been a replay, Klein would have refereed the World Cup final at the age of 48. Italy won 3-1.

So now then

Klein retired in 1984, at the age of 50. He would later be chairman of the referees committee in Israel, and a Fifa referees instructor. He also refereed at the Special Olympics in 1995 and 1999. Now 77, he has the chance to experience the globe, not just colour it in on a map, and to enjoy the friendships fostered through football. “It’s unbelievable,” he says. “What refereeing has done for me is not only about the games, and not only that I saw the world – because when I was a referee I travelled around the world but I didn’t see nothing from the world. Today if I land anywhere in the world somebody is waiting for me. It’s a good feeling, and when they come to Israel I do the same, believe me.”

He goes everywhere with his wife Bracha. “I have a wonderful wife, believe me. She accompanies me around the world.” Last year they went on a cruise from Rome, first stopping off at the same hotel that Klein had stayed in before the Poland game in 1965. “In reception there was a man, not old but maybe 60. I give him my passport He look my passport, he look my passport, he look my face. ‘82, Italia-Brasil!’ He look me. I told him, ‘Yes, Italia-Brasil’. He give me my key. It was a pre-paid room. We get the lift and go to our room. It was a suite, an unbelievable suite. I told my wife, we go back to the luggage, it was a mistake. I did not pay for a suite, I pay for an ordinary room. I go back, I told him, ‘We are very sorry, I pay for another room’. ‘Nonononono, it is our great pleasure that you stay in our hotel’. Then he sent to our room wine and chocolate. Unbelievable.”

Klein still lives in Haifa, close to his daughter and his granddaughters. “I am living in an apartment hotel, very close to the sea. I feel the winter air.” He still does around three hours’ exercise a day: swimming, gym work or just walking along the bench. Even now, as he approaches his ninth decade on earth, he sticks to his fighting weight. “I am very fit today. I am 65 kilos (just over 10st), the same as when I refereed England v Brazil. When I go on a cruise I put on two or three kilos because they feed you 24 hours a day, but when I get home I work it off. I am a very rich man. You know why? I don’t need to buy any clothes! Not the same shoes but the same clothes …”

Then there are the leisure pursuits for which there was so little time during his career. “I tell you I am very busy. I am busy with my training, with my family, with reading books, going to concerts or the opera, meeting friends. I love sport, I play tennis I watch sport every day, NBA, English football. I am a happy man I can tell you, very happy. And if I am looking back, I am very happy with my career. Very, very happy.”

There is no arrogance, just pride and still, perhaps, a hint of incredulity at this unbelievable life. He does not need the validation of being called the best referee of all time. He gets validation every time he looks in his museum, or every time he flies to a different part of the world and is introduced as the man who refereed England v Brazil in 1970. It’s enough to say that Klein was one of the greatest referees of all time. And that he has lived a life like no other.

Thanks to Abraham Klein, Dan Friedman and Cris Freddi.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion